They say the plot of every opera is that the soprano wants to sleep with the tenor, but the baritone won’t let her. See, for example, Rigoletto, or La Traviata, or even Carmen. My idea, and I’ll ask — nay, even beg — for forgiveness later, was to use AI tools to generate the rough form of such an opera.

I’m primarily a Java developer, so I wanted to code all this in Java. For that there are a couple of frameworks available to make the process easier. One of the best is called LangChain4j, and it not only makes it easy to work with multiple AI tools together, but it has classes for managing the required memory, generating images, and more. Given that, the process I followed was:

- Use two AI tools, namely OpenAI’s GPT-4o and Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet, and have them alternate writing scenes.

- Programmatically manage the chat memory, passing the results of each scene to the other.

- Feed the individual scenes into the DALL-E 3 image generator and use it to illustrate the libretto.

- Use the Suno AI song generator to create music for the beginning of the first scene, since that fits nicely inside the free tier.

If you ever worked with AI tools programmatically, you know that every request is stateless. In other words, each request is completely independent of every other. Using the web site doesn’t feel like that, because the underlying code on the site manages the conversations for you. If you do it yourself, the default is for the AI tool to remember nothing from request to request.

Me, to AI: My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.

AI: Hi Inigo. I hope you find the six-fingered man.

Me: What’s my name?

AI: I’m sorry, but I don’t have access to personal information about you unless you’ve shared it during our conversation. If you’d like to tell me your name, feel free to share!

(I have a whole video on that, and a blog post, if you’re interested.)

The way you fix the memory issue with LangChain4j is to use a class they call, naturally enough, ChatMemory. Chat messages (both requests and responses) from the memory object are passed along with each new query. Each subsequent query gets more expensive that way, but tokens are cheap and this is the only way to get the tool to “remember” what was already said. There’s a maximum number of tokens available, which AI tools call the context window, but that’s grown pretty large in recent versions. For example, both GPT-4o and Claude have a context window of about 128K tokens.

(Some quick math: 1000 tokens is approximately 750 words in English. The cost of 1000 input tokens is about a penny and a half, and the cost of 1000 output tokens is about one-tenth of that. My entire generated libretto is just over 5000 words, which is about 4000 tokens, so I spent about a nickel on it, or maybe a dime with all the iterations. Pictures are 4 cents an image, so I splurged an additional 20 cents for five of them, one per scene.)

Here’s the code to set up the two AI tools:

public final ChatLanguageModel gpt4o =

OpenAiChatModel.builder()

.apiKey(ApiKeys.OPENAI_API_KEY)

.modelName(OpenAiChatModelName.GPT_4_O)

.build();

public final ChatLanguageModel claude =

AnthropicChatModel.builder()

.apiKey(ApiKeys.ANTHROPIC_API_KEY)

.modelName(

AnthropicChatModelName.CLAUDE_3_SONNET_20240229)

.build();

My two required keys — one for GPT-4o and one for Claude — are saved as environment variables in my system.

Here’s the beginning of my method to generate the scenes. I use the ChatMemory interface in LangChain4j to save the last 10 messages, assuming they fit into the context window (which, in this case, they do comfortably).

ChatMemory memory =

MessageWindowChatMemory.withMaxMessages(10);

memory.add(SystemMessage.from("""

They say that all operas are about a soprano

who wants to sleep with the tenor, but the

baritone won't let her.

You are composing the libretto for such an opera.

The setting is the wild jungles of Connecticut,

in the not-so-distant future after global

warming has reclaimed the land.

The soprano is an intrepid explorer searching

for the lost city of Hartford. The tenor is a

native poet who has been living in the jungle

for years, writing sonnets to the trees and

composing symphonies for the monkeys.

The baritone is a government agent who has been

sent to stop the soprano from finding the lost

city. He has a secret weapon: a giant robot that

can sing Verdi arias in three different languages.

The soprano and the tenor meet in the jungle and

fall in love. They decide to join forces and find

the lost city together. But the baritone is always

one step behind them, and his giant robot is

getting closer and closer.

"""));

Some of that is my idea (I live relatively close to Hartford, CT, the Insurance Capital of the World). The rest was auto-generated by my GitHub Copilot plugin inside of IntelliJ IDEA, which suggested the giant robot, among other things.

Here’s the code that manages the ChatMemory and passes each response back to the next tool:

UserMessage userMessage = UserMessage.from("""

Please write the next scene.

""");

memory.add(userMessage);

ChatLanguageModel model;

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

model = i % 2 == 0 ? gpt4o : claude;

AiMessage response =

model.generate(memory.messages()).content();

System.out.println(response.text());

memory.add(response);

memory.add(userMessage);

}

I pass all the messages inside ChatMemory to each tool, along with the user message “Please write the next scene,” and off we go.

Here’s the beginning of the result, which for some strange reason started with Scene 2:

### Scene 2: The Heart of the Jungle

> **Author: OpenAiChatModel**

*The curtain rises to reveal a lush, overgrown jungle setting. The sound of exotic birds and distant waterfalls fills the air. In the middle of the stage, a clearing is visible with ancient, vine-covered ruins hinting at the lost city of Hartford. The soprano, **Elena**, dressed in rugged explorer's attire, is carefully examining an old map. The tenor, **Rafael**, barefoot and adorned with natural elements, is composing music on a makeshift wooden instrument. They are completely absorbed in their tasks.*

**Elena**: *(Singing, with a sense of determination and curiosity)*

In this verdant maze, we seek the past,

Where whispers of a city long have cast

Their shadows on our hearts and dreams,

In Hartford's ruins, find what seems.

**Rafael**: *(Responding, with a poetic and melodic air)*

Oh Elena, your courage lights the way,

Through tangled vines and night and day.

In sonnets, I have penned this quest,

To find the city where our hearts may rest.

*They join hands and sing together, their voices blending in harmony.*

**Elena & Rafael**: *(Duet)*

Together, we shall brave the wild,

With love and hope, our hearts are mild.

In Hartford's ancient, hidden halls,

We'll write our story on its walls.

Um, yeah. The results are pretty wild. The climax involves the soprano singing to distract the baritone while the tenor leaps from a tree behind him and steals the robot’s remote control. Seriously.

Both AI tools generate responses in markdown format. The entire libretto is in this GitHub repository, which holds most of my LangChain4j examples. The direct link to the libretto is here. The browser renders markdown correctly, so it’s easy to follow there.

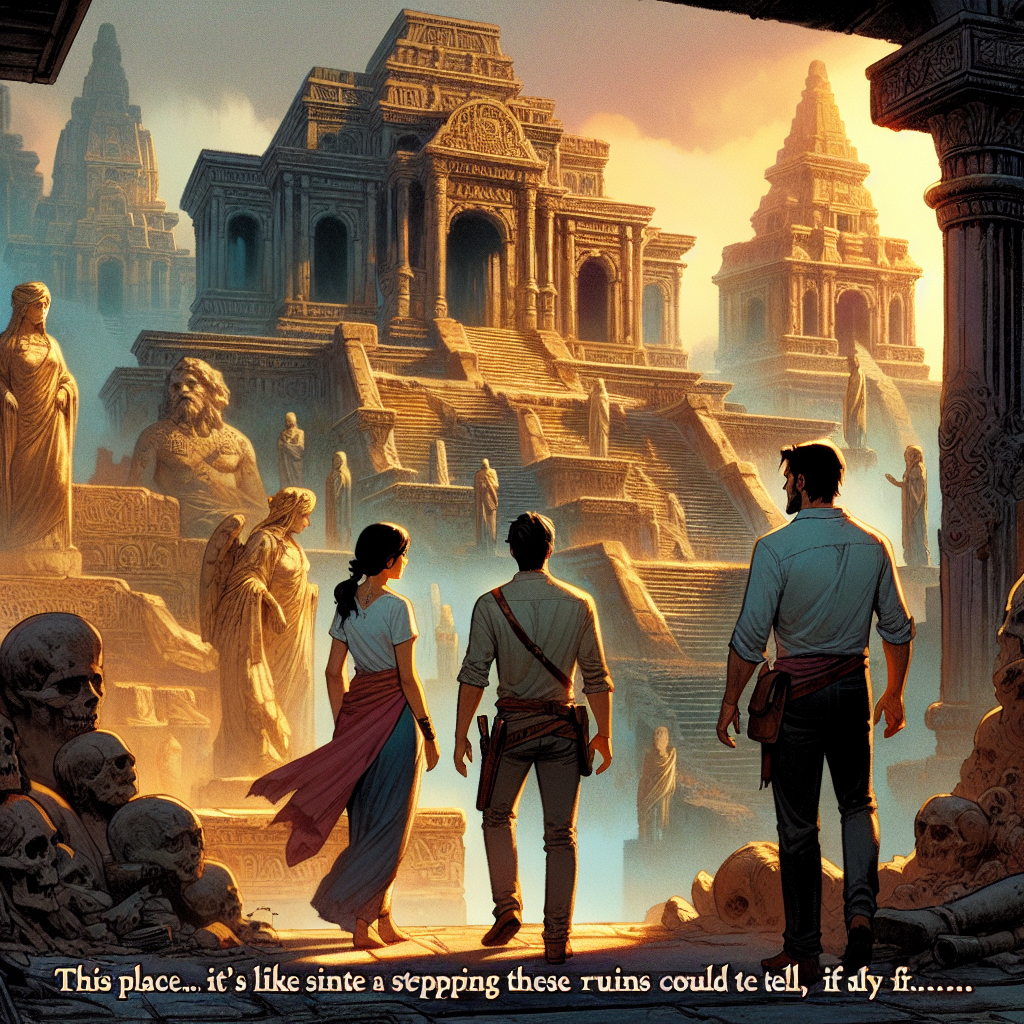

You might have noticed the inclusion of an image in the syntax. After the scenes were generated, I used the framework to contact DALL-E 3 and create an image for each scene:

var model = OpenAiImageModel.builder()

.apiKey(ApiKeys.OPENAI_API_KEY)

.persistTo(Paths.get(RESOURCE_PATH))

.build();

sceneContents.forEach((fileName, content) -> {

String prompt = generatePrompt(fileName, content);

model.generate(prompt);

}

The OpenAiImageModel connects to DALL-E 3, and automatically saves the resulting png file into my RESOURCE_PATH, which is just src/main/resources on my disk. The actual prompt is something like, “Create an image for Scene {number] using {description},” and so on. The rest of the code is about renaming the generated image files to appropriate names, and then adding them to the libretto.

Most of the images are not very closely related to the text, but at least one has a robot in it:

Cartoon-y, but okay, at least it has a robot. Here’s another one:

Yeah, I know. The resemblance to the real Hartford is uncanny. And by uncanny, I mean uncanny valley.

The part I could not do programmatically was generate the music. OpenAI does include a Text-to-Speech (TTS) API, and it’s really easy to use, but it doesn’t generate music. For the music sample, I went to Suno, pasted in the snippet included above, and this was (one of) the results:

I entered the genre as opera, but this is what I got instead. It interpreted one of the blocking instructions as lyrics, but so be it. It’s even got a guitar solo in it, so it’s got that going for it, which is nice. Let me know in the comments if you think I should continue this silliness, or if this is definitely far enough.

Feel free to check out Whispers of the Lost Hartford, coming soon absolutely nowhere, assuming there’s any justice at all left in the world. You’re welcome to the code (it’s under the MIT License), but if you try it out with AI tools and don’t like the results, the Secretary will disavow all knowledge of you and your team, etc.

In the meantime, have fun!

Leave a Reply